Flow Through a Nacelle in a Crosswind

At Georgia Tech, I had the opportunity to join the Fluid Mechanics Research Lab and research under Professor Ari Glezer. The Boeing Company had funded a new research project to study how crosswinds affect the inflow through an aircraft nacelle and helped to commission a dedicated wind tunnel at Georgia Tech in order to study this interaction. When the project officially started, I was lucky enough to be in a position to take it on as the lead student.

Aircraft in crosswinds close to the ground are of significant interest as the crosswind speed still holds a meaningful velocity component with respect to the slowly moving aircraft. Because of this, two different flow features can form: inlet flow separation on the inner windward side of the nacelle and a ground vortex. These features result in substantial distortion through the inlet which leads to asymmetric flow, blade vibrations, and possibly engine stall. In addition, the ground vortex can pick objects up off the ground and ingest them into the engine which can cause catastrophic damage. It is therefore desired to better understand how this flow behaves and to attempt to minimize these adverse effects using various flow control techniques.

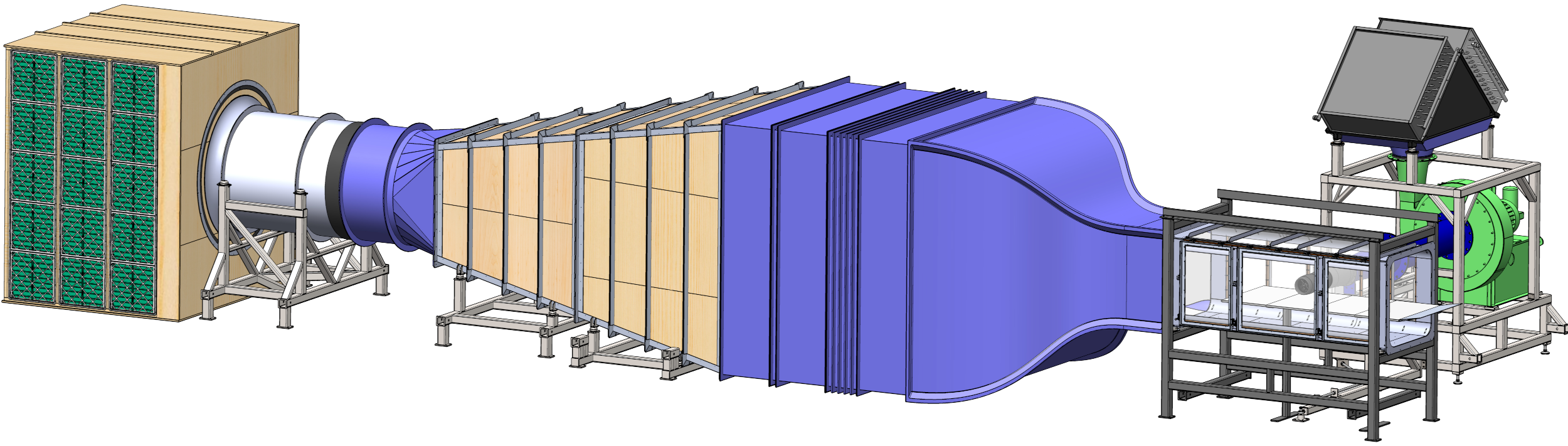

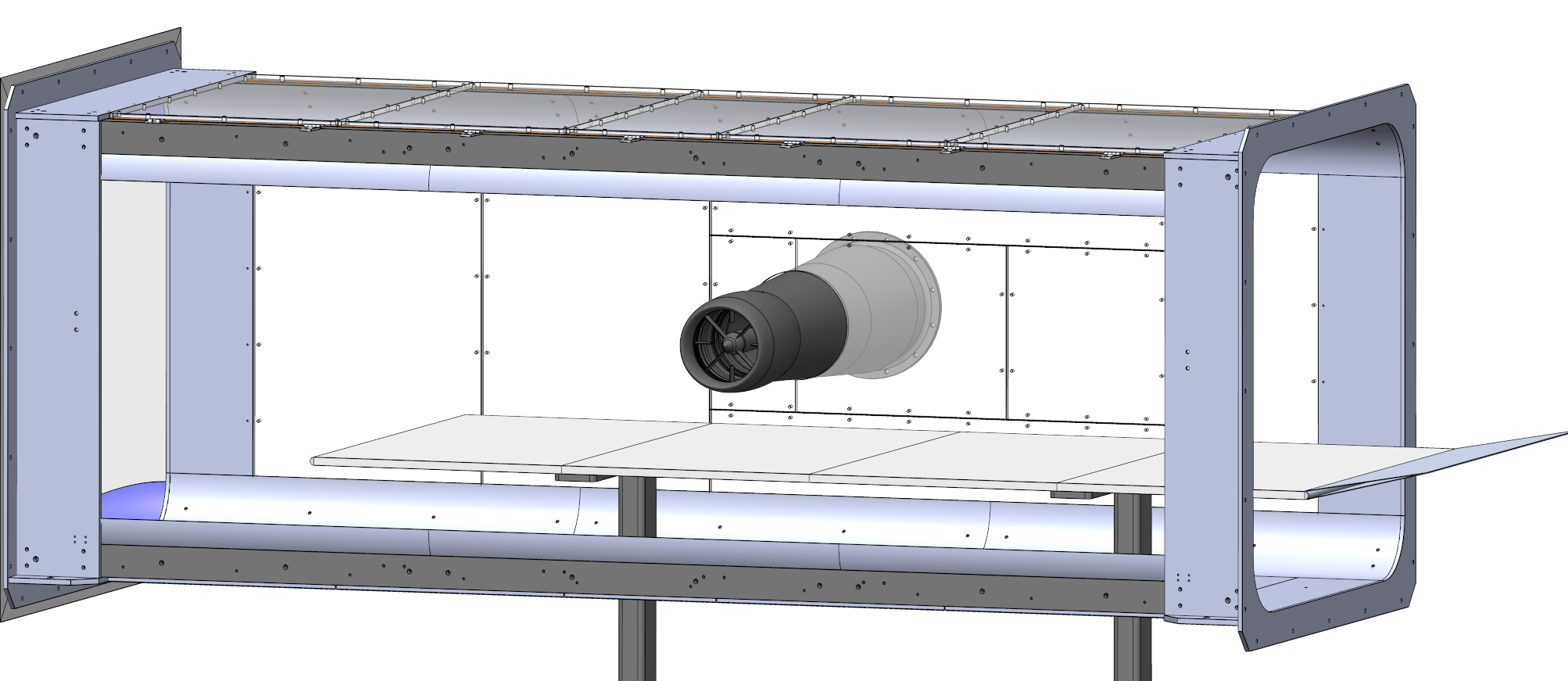

The facility at Georgia Tech consisted of two primary components: a model nacelle assembly and a cross flow wind tunnel. The flow through each component is independently varied, and the position and orientation of the nacelle within the tunnel's test section is variable. For study of the ground vortex phenomena, the floor of the test section was replaced with a moveable ground plane. The nacelle model is mounted on a flow duct that is driven in suction by a dedicated, computer-controlled blower. Various diagnostic techniques are used to assess the flow through the inlet including a total pressure rake just downstream of the inlet entrance, static pressure ports on the wall near the entrance, mass flow measurements via an averaging pitot probe just upstream of the blower, particle image velocimetry (PIV) measurements, and surface oil flow visualization.

|

|

After fully characterizing the base flow of the model for an array of inlet mass flow rates and crosswind speeds, the next task was to determine what could be done to alleviate the adverse effects that were initiated with the introduction of the crosswind. The first method of flow control that was tried was the use of autonomous bleed to selectively move air from the outside in along the preexisting pressure gradient. By doing so, the air moving along the wall creates a new "virtual surface" so that the main body of incoming air has a better chance of remaining attached. Results which are discussed in the Journal of Propulsion and Power have shown that the distortion can be significantly reduced be simply opening selective passages through the inlet for air to move. The major drawback of this technology is that its effectiveness is directly dependent on the mass flow rate through the inlet. Instead using active jets that would utilize bypassed air through the engine allows for enhanced performance at even the lowest flow rates. Results have been discussed in two conference papers (AIAA Aviation 2020 and AIAA SciTech 2021) with a journal publication in draft.

In regard to the ground vortex, my research uncovered a new mechanism for its formation. As the inlet flow rate initially increases, a countercurrent shear layer eventually forms on the leeward side of the inlet between the flow moving into the inlet and the cross flow moving in the opposite direction. Vortices periodically form in this shear layer due to a Kelvin-Helmholtz instability and move in the direction of the average velocity in the shear layer. As the mass flow rate increases further, the vortex ultimately ingests vorticity off the ground surface from the ground boundary layer. To prevent the formation of the ground vortex, my research showed that one must delay this initial interaction with the ground surface. To accomplish this, the bleed inlet was repurposed which effectively increases the area of the inlet and decreases the average velocity through the inlet while still maintaining the same mass flow rate. Through the optimal configuration, the onset of the ground vortex was able to be delayed to over 300% of the uncontrolled inlet momentum flux by favoring flow away from the ground surface. More details about this work can be found in the Journal of Fluid Mechanics and the AIAA Journal.

This research generated significant interest in the scientific community. In 2019, I was awarded a three year fellowship through the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program to continue studying this problem. In addition, I was also awarded one of two Orville and Wilbur Wright Graduate Awards through AIAA in 2019. Both of these awards have greatly helped me in furthering the study of nacelles in crosswinds.